Tech

Trump Likely to Extend TikTok Ban Deadline Amid Broader China Negotiations

U.S. President Donald Trump is expected to grant a third extension to TikTok’s Chinese parent company, ByteDance, giving it an additional 75 days to find an American buyer or face a nationwide ban. The deadline, originally set for June 19, stems from a Supreme Court decision mandating the app’s divestment on national security grounds.

Trump told reporters Tuesday that he would “probably” extend the deadline again, but hinted the move might require China’s President Xi Jinping’s approval — a signal that the social media platform is now entangled in wider U.S.–China geopolitical negotiations.

The extension comes amid shifting global trade dynamics. Trump recently claimed progress on a new U.S.–China trade agreement, which reportedly includes the exchange of rare earth minerals for reduced tariffs and allowances for Chinese students at American universities. Some analysts see the TikTok ban as part of these broader trade talks, used as leverage to extract concessions.

“Tying TikTok to negotiations with China isn’t new,” said Darío García de Viedma, a digital policy expert at Spain’s Elcano Royal Institute. “Trump appears to be using TikTok as a bargaining chip — much like India did in 2020 when it banned the app following border clashes with China.”

While India’s TikTok ban was a show of sovereignty, Trump’s approach differs rhetorically. “Trump is telling the public, ‘I’m going to save TikTok,’ but the strategy mirrors India’s—it’s a populist tool to assert control,” García de Viedma added.

Despite national security concerns cited by U.S. lawmakers, the extent of actual data risk remains debated. Critics argue that other U.S.-based platforms engage in similar data collection practices. “All social media apps are security risks because of the way they harvest data,” said Jan Penfrat, senior advisor at European Digital Rights. “This isn’t uniquely about China—it’s about the advertising-driven business model.”

Questions also remain about the potential sale: Would ByteDance be required to sell TikTok’s algorithm or just its U.S. operations? If the algorithm stays in China, it could fundamentally change what users in the U.S. and beyond see on their feeds. Such a change could disrupt the massive creator-driven “TikTok economy,” especially in the U.S.

García de Viedma suggested the uncertainty itself may be part of Trump’s strategy—to destabilize the app’s user base and influence, pushing creators toward U.S. platforms like Instagram and weakening TikTok’s value ahead of a potential sale.

Whether an extension is granted this week or not, TikTok’s fate in the U.S. remains inextricably linked to a broader game of tech, trade, and geopolitical influence.

Tech

Northvolt Collapse Raises Questions Over Europe’s Green Tech Ambitions

Tech

ESA and GSMA Launch €100 Million Initiative to Advance Europe’s 6G and AI Ambitions

Europe has stepped up its push to lead in next-generation connectivity with a new partnership between the European Space Agency and the GSMA aimed at strengthening 6G and artificial intelligence capabilities through satellite-based communications.

The two organisations announced at the Mobile World Congress a joint funding programme worth up to €100 million to accelerate the integration of satellite and terrestrial mobile networks, known as non-terrestrial networks (NTN). The initiative marks one of Europe’s most significant public investments to date in hybrid satellite-mobile infrastructure.

Antonio Franchi, head of the 5G/6G NTN Programme Office at ESA, described connectivity as the backbone for unlocking advanced technologies. He said the funding would support the development of networks, services and digital tools that could benefit industries and society at large as digital transformation expands.

The programme is open to companies and organisations based in EU member states, which can apply by submitting formal proposals to ESA. Projects will be selected following an evaluation process.

Funding will focus on four core areas: artificial intelligence-driven management of multi-orbit satellite and ground networks; direct-to-device connectivity for smartphones and Internet of Things devices; collaborative 5G and 6G testing platforms; and early research into edge intelligence and advanced IoT systems.

The types of applications envisioned include telemedicine and telesurgery, autonomous driving systems and precision agriculture, all of which depend on reliable, high-capacity connectivity. By merging satellite coverage with mobile infrastructure, the initiative aims to extend high-speed communication even to remote regions.

Alex Sinclair, chief technology officer at GSMA, said combining the mobile industry’s global reach with ESA’s expertise in space technology would help usher in a new era of connectivity and deliver transformative benefits.

The move comes as global competition intensifies in satellite internet and advanced communications, with US companies currently holding a strong position. European officials say the continent’s strength in high-tech manufacturing and specialised software can offer an independent and competitive alternative.

Several European firms are showcasing their work under the programme at MWC, including Nokia, Filtronic, OQ Technology and MinWave Technologies. Demonstrations include live displays of hybrid network architectures and orchestration of satellite-terrestrial systems.

A centrepiece of the exhibition highlights Europe’s space ambitions through a mixed-reality model of ESA’s Argonaut lunar lander, designed to deliver cargo to the Moon. Visitors can remotely operate a training rover via a live satellite link, underscoring how Europe’s connectivity infrastructure is intended to support not only terrestrial innovation but also future lunar missions.

Tech

Mobile World Congress Opens in Barcelona With Focus on AI and 5G Concerns

-

Entertainment2 years ago

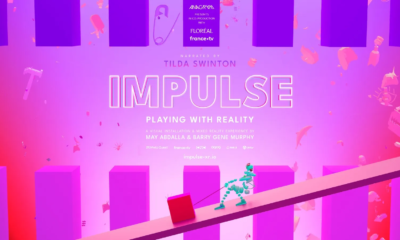

Entertainment2 years agoMeta Acquires Tilda Swinton VR Doc ‘Impulse: Playing With Reality’

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia’s Model for Sustainable Aviation Practices

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoRecent Developments in Small Business Taxes

-

Home Improvement1 year ago

Home Improvement1 year agoEffective Drain Cleaning: A Key to a Healthy Plumbing System

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoWho was Ebrahim Raisi and his status in Iranian Politics?

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoCarrectly: Revolutionizing Car Care in Chicago

-

Sports2 years ago

Sports2 years agoKeely Hodgkinson Wins Britain’s First Athletics Gold at Paris Olympics in 800m

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia: Foreign Direct Investment Rises by 5.6% in Q1