Tech

Red Sea Undersea Cable Cuts Disrupt Internet Across Middle East and Asia

Two major subsea cables linking Europe to the Middle East and Asia were reportedly severed in the Red Sea over the weekend, disrupting internet services across parts of the Middle East, South Asia and beyond. The cause of the incident remains unclear, though analysts say the region’s heavy maritime traffic and geopolitical tensions make the undersea network particularly vulnerable.

Cybersecurity watchdog NetBlocks confirmed outages on Sunday, attributing the disruption to failures on the South East Asia-Middle East-Western Europe 4 (SMW4) and India-Middle East-Western Europe (IMEWE) cable systems near Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The two cables form part of the global backbone of the internet, carrying vast amounts of international data traffic between Europe and Asia.

“The subsea cable outages in the Red Sea have degraded internet connectivity in multiple countries,” NetBlocks said, naming India and Pakistan among the most affected. Users in the United Arab Emirates also reported slower browsing and difficulties with streaming and messaging apps on state-owned providers Etisalat and Du.

Kuwaiti officials confirmed that the FALCON GCX cable was also cut, compounding disruptions in the Gulf state. However, telecom operator GCX has not publicly commented. In Saudi Arabia, where the damage reportedly occurred, officials have yet to acknowledge the incident.

The SMW4 cable, an 18,800-kilometre system operational since 2005, connects France and Italy to countries across North Africa and Asia, including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, India, Pakistan and Singapore. The project, which cost $500 million, was jointly built by France’s Alcatel Submarine Networks and Japan’s Fujitsu. The IMEWE cable, launched in 2010 at a cost of $480 million, spans more than 12,000 kilometres, linking Europe to India through the Middle East.

The Red Sea is one of the world’s most critical digital corridors, carrying around 17 per cent of global internet traffic, according to telecom research firm TeleGeography. Even localised faults can ripple across continents, impacting cloud services, banking platforms and airline systems.

Speculation over possible sabotage has heightened since Yemen’s Houthi rebels launched attacks on shipping in the Red Sea as part of their campaign to pressure Israel over the war in Gaza. While the group has previously denied targeting undersea infrastructure, concerns remain over the cables’ vulnerability.

The International Cable Protection Committee estimates there are around 1.7 million kilometres of undersea cables worldwide, with 150 to 200 incidents recorded annually. Most are caused by human activity, such as fishing or ship anchors, while the remainder are linked to natural hazards like earthquakes.

Repairing damaged cables is a complex and costly process that can take weeks. With no immediate clarity on the cause of the Red Sea cuts or a timeline for repairs, millions of users across the region may continue to face disruptions in the coming days.

Tech

Northvolt Collapse Raises Questions Over Europe’s Green Tech Ambitions

Tech

ESA and GSMA Launch €100 Million Initiative to Advance Europe’s 6G and AI Ambitions

Europe has stepped up its push to lead in next-generation connectivity with a new partnership between the European Space Agency and the GSMA aimed at strengthening 6G and artificial intelligence capabilities through satellite-based communications.

The two organisations announced at the Mobile World Congress a joint funding programme worth up to €100 million to accelerate the integration of satellite and terrestrial mobile networks, known as non-terrestrial networks (NTN). The initiative marks one of Europe’s most significant public investments to date in hybrid satellite-mobile infrastructure.

Antonio Franchi, head of the 5G/6G NTN Programme Office at ESA, described connectivity as the backbone for unlocking advanced technologies. He said the funding would support the development of networks, services and digital tools that could benefit industries and society at large as digital transformation expands.

The programme is open to companies and organisations based in EU member states, which can apply by submitting formal proposals to ESA. Projects will be selected following an evaluation process.

Funding will focus on four core areas: artificial intelligence-driven management of multi-orbit satellite and ground networks; direct-to-device connectivity for smartphones and Internet of Things devices; collaborative 5G and 6G testing platforms; and early research into edge intelligence and advanced IoT systems.

The types of applications envisioned include telemedicine and telesurgery, autonomous driving systems and precision agriculture, all of which depend on reliable, high-capacity connectivity. By merging satellite coverage with mobile infrastructure, the initiative aims to extend high-speed communication even to remote regions.

Alex Sinclair, chief technology officer at GSMA, said combining the mobile industry’s global reach with ESA’s expertise in space technology would help usher in a new era of connectivity and deliver transformative benefits.

The move comes as global competition intensifies in satellite internet and advanced communications, with US companies currently holding a strong position. European officials say the continent’s strength in high-tech manufacturing and specialised software can offer an independent and competitive alternative.

Several European firms are showcasing their work under the programme at MWC, including Nokia, Filtronic, OQ Technology and MinWave Technologies. Demonstrations include live displays of hybrid network architectures and orchestration of satellite-terrestrial systems.

A centrepiece of the exhibition highlights Europe’s space ambitions through a mixed-reality model of ESA’s Argonaut lunar lander, designed to deliver cargo to the Moon. Visitors can remotely operate a training rover via a live satellite link, underscoring how Europe’s connectivity infrastructure is intended to support not only terrestrial innovation but also future lunar missions.

Tech

Mobile World Congress Opens in Barcelona With Focus on AI and 5G Concerns

-

Entertainment2 years ago

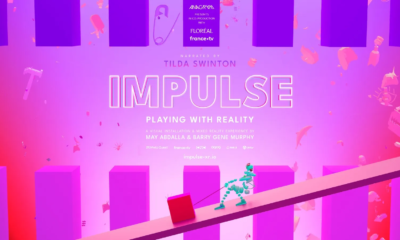

Entertainment2 years agoMeta Acquires Tilda Swinton VR Doc ‘Impulse: Playing With Reality’

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia’s Model for Sustainable Aviation Practices

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoRecent Developments in Small Business Taxes

-

Home Improvement1 year ago

Home Improvement1 year agoEffective Drain Cleaning: A Key to a Healthy Plumbing System

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoWho was Ebrahim Raisi and his status in Iranian Politics?

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoCarrectly: Revolutionizing Car Care in Chicago

-

Sports2 years ago

Sports2 years agoKeely Hodgkinson Wins Britain’s First Athletics Gold at Paris Olympics in 800m

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia: Foreign Direct Investment Rises by 5.6% in Q1