Tech

Study Finds Most People Can No Longer Tell AI-Generated Voices from Real Ones

A new study has found that most people can no longer distinguish between human voices and their artificial intelligence (AI)-generated counterparts, raising growing concerns about misinformation, fraud, and the ethical use of voice-cloning technologies.

The research, published in the journal PLoS One by scientists from Queen Mary University of London, revealed that participants were able to correctly identify genuine human voices only slightly more often than they could identify cloned AI voices. Out of 80 voice samples—half human and half AI-generated—participants mistook 58 percent of cloned voices for real, while 62 percent of actual human voices were correctly identified.

“The most important aspect of the research is that AI-generated voices, specifically voice clones, sound as human as recordings of real human voices,” said Dr. Nadine Lavan, lead author of the study and senior lecturer in psychology at Queen Mary University. She added that these realistic voices were created using commercially available tools, meaning anyone can produce convincing replicas without advanced technical skills or large budgets.

AI voice cloning works by analyzing vocal data to capture and reproduce unique characteristics such as tone, pitch, and rhythm. This precise imitation has made the technology increasingly popular among scammers, who use cloned voices to impersonate loved ones or public figures. According to research by the University of Portsmouth, nearly two-thirds of people over 75 have received attempted phone scams, with about 60 percent of those attempts made through voice calls.

The spread of AI-generated “deepfake” audio has also been used to mimic politicians, journalists, and celebrities, raising fears about its potential to manipulate public opinion and spread false information.

Dr. Lavan urged developers to adopt stronger ethical safeguards and work closely with policymakers. “Companies creating the technology should consult ethicists and lawmakers to address issues around voice ownership, consent, and the legal implications of cloning,” she said.

Despite its risks, researchers say the technology also has significant potential for positive impact. AI-generated voices can help restore speech to people who have lost their ability to speak or allow users to design custom voices that reflect their identity.

“This technology could transform accessibility in education, media, and communication,” Lavan noted. She highlighted examples such as AI-assisted audio learning, which has been shown to improve reading engagement among students with neurodiverse conditions like ADHD.

Lavan and her team plan to continue studying how people interact with AI-generated voices, exploring whether knowing a voice is artificial affects trust, engagement, or emotional response.

“As AI voices become part of our daily lives, understanding how we relate to them will be crucial,” she said.

Tech

Northvolt Collapse Raises Questions Over Europe’s Green Tech Ambitions

Tech

ESA and GSMA Launch €100 Million Initiative to Advance Europe’s 6G and AI Ambitions

Europe has stepped up its push to lead in next-generation connectivity with a new partnership between the European Space Agency and the GSMA aimed at strengthening 6G and artificial intelligence capabilities through satellite-based communications.

The two organisations announced at the Mobile World Congress a joint funding programme worth up to €100 million to accelerate the integration of satellite and terrestrial mobile networks, known as non-terrestrial networks (NTN). The initiative marks one of Europe’s most significant public investments to date in hybrid satellite-mobile infrastructure.

Antonio Franchi, head of the 5G/6G NTN Programme Office at ESA, described connectivity as the backbone for unlocking advanced technologies. He said the funding would support the development of networks, services and digital tools that could benefit industries and society at large as digital transformation expands.

The programme is open to companies and organisations based in EU member states, which can apply by submitting formal proposals to ESA. Projects will be selected following an evaluation process.

Funding will focus on four core areas: artificial intelligence-driven management of multi-orbit satellite and ground networks; direct-to-device connectivity for smartphones and Internet of Things devices; collaborative 5G and 6G testing platforms; and early research into edge intelligence and advanced IoT systems.

The types of applications envisioned include telemedicine and telesurgery, autonomous driving systems and precision agriculture, all of which depend on reliable, high-capacity connectivity. By merging satellite coverage with mobile infrastructure, the initiative aims to extend high-speed communication even to remote regions.

Alex Sinclair, chief technology officer at GSMA, said combining the mobile industry’s global reach with ESA’s expertise in space technology would help usher in a new era of connectivity and deliver transformative benefits.

The move comes as global competition intensifies in satellite internet and advanced communications, with US companies currently holding a strong position. European officials say the continent’s strength in high-tech manufacturing and specialised software can offer an independent and competitive alternative.

Several European firms are showcasing their work under the programme at MWC, including Nokia, Filtronic, OQ Technology and MinWave Technologies. Demonstrations include live displays of hybrid network architectures and orchestration of satellite-terrestrial systems.

A centrepiece of the exhibition highlights Europe’s space ambitions through a mixed-reality model of ESA’s Argonaut lunar lander, designed to deliver cargo to the Moon. Visitors can remotely operate a training rover via a live satellite link, underscoring how Europe’s connectivity infrastructure is intended to support not only terrestrial innovation but also future lunar missions.

Tech

Mobile World Congress Opens in Barcelona With Focus on AI and 5G Concerns

-

Entertainment2 years ago

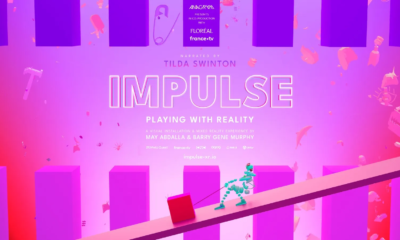

Entertainment2 years agoMeta Acquires Tilda Swinton VR Doc ‘Impulse: Playing With Reality’

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia’s Model for Sustainable Aviation Practices

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoRecent Developments in Small Business Taxes

-

Home Improvement1 year ago

Home Improvement1 year agoEffective Drain Cleaning: A Key to a Healthy Plumbing System

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoWho was Ebrahim Raisi and his status in Iranian Politics?

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoCarrectly: Revolutionizing Car Care in Chicago

-

Sports2 years ago

Sports2 years agoKeely Hodgkinson Wins Britain’s First Athletics Gold at Paris Olympics in 800m

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia: Foreign Direct Investment Rises by 5.6% in Q1