Tech

Record 4,325 Submissions Reveal Sharp Divide Over EU’s Digital Fairness Act

The European Commission’s public consultation on the proposed Digital Fairness Act (DFA) has drawn a record 4,325 submissions, underscoring a growing divide between Europe’s business community and publicly funded non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

The high volume of feedback — boosted by hundreds of gamers concerned about the Act’s potential impact — reflects the controversy surrounding the Commission’s plans to tighten rules on digital consumer protection. While most business groups have opposed the proposal, many civic organisations have voiced strong support.

The DFA, spearheaded by Irish Commissioner Michael McGrath, aims to modernise EU consumer laws to address issues unique to the digital economy. Its current scope includes regulating “dark patterns” (manipulative online design), misleading influencer marketing, “addictive” digital product designs, and unfair personalisation practices.

Critics warn, however, that vague definitions — particularly of “addictive design” and “dark patterns” — could allow regulators to target digital platforms arbitrarily. Businesses also fear that the Act could amount to a de facto ban on personalised advertising, a change that would reshape the EU’s digital economy.

Leading European firms, including Wolt, Ryanair, Vinted, and Spotify, have urged the Commission to prioritise enforcement of existing rules rather than layering new regulations. They argue that over-regulation could drive up advertising costs, reduce reach for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and make ads less relevant for consumers.

“Europe’s digital champions are asking for balance,” said one industry representative. “We already have some of the world’s strictest consumer and data protection laws — what we need now is consistent enforcement, not another layer of complexity.”

Indeed, the EU already enforces a wide array of digital regulations, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Digital Services Act (DSA), Digital Markets Act (DMA), and the Consumer Rights Directive. Many stakeholders argue that the real challenge lies in fragmented enforcement across member states, not in the absence of rules.

The Commission has justified the DFA by citing an estimated €7.9 billion in annual financial harm to consumers from online problems. However, business groups counter that the figure has not been weighed against the economic benefits of personalised advertising, which they say contributes over €25 billion to EU GDP and supports around 600,000 jobs.

Proponents of stricter regulation argue that Europeans are increasingly concerned about how their personal data is used online. Yet studies suggest most consumers still prefer relevant, personalised ads. As the Commission prepares its impact assessment, both sides are calling for a more balanced evaluation of consumer interests and economic realities.

The Digital Fairness Act remains in early stages, but with thousands of submissions and mounting scrutiny, the debate over the future of digital consumer protection in Europe is only just beginning.

Tech

Northvolt Collapse Raises Questions Over Europe’s Green Tech Ambitions

Tech

ESA and GSMA Launch €100 Million Initiative to Advance Europe’s 6G and AI Ambitions

Europe has stepped up its push to lead in next-generation connectivity with a new partnership between the European Space Agency and the GSMA aimed at strengthening 6G and artificial intelligence capabilities through satellite-based communications.

The two organisations announced at the Mobile World Congress a joint funding programme worth up to €100 million to accelerate the integration of satellite and terrestrial mobile networks, known as non-terrestrial networks (NTN). The initiative marks one of Europe’s most significant public investments to date in hybrid satellite-mobile infrastructure.

Antonio Franchi, head of the 5G/6G NTN Programme Office at ESA, described connectivity as the backbone for unlocking advanced technologies. He said the funding would support the development of networks, services and digital tools that could benefit industries and society at large as digital transformation expands.

The programme is open to companies and organisations based in EU member states, which can apply by submitting formal proposals to ESA. Projects will be selected following an evaluation process.

Funding will focus on four core areas: artificial intelligence-driven management of multi-orbit satellite and ground networks; direct-to-device connectivity for smartphones and Internet of Things devices; collaborative 5G and 6G testing platforms; and early research into edge intelligence and advanced IoT systems.

The types of applications envisioned include telemedicine and telesurgery, autonomous driving systems and precision agriculture, all of which depend on reliable, high-capacity connectivity. By merging satellite coverage with mobile infrastructure, the initiative aims to extend high-speed communication even to remote regions.

Alex Sinclair, chief technology officer at GSMA, said combining the mobile industry’s global reach with ESA’s expertise in space technology would help usher in a new era of connectivity and deliver transformative benefits.

The move comes as global competition intensifies in satellite internet and advanced communications, with US companies currently holding a strong position. European officials say the continent’s strength in high-tech manufacturing and specialised software can offer an independent and competitive alternative.

Several European firms are showcasing their work under the programme at MWC, including Nokia, Filtronic, OQ Technology and MinWave Technologies. Demonstrations include live displays of hybrid network architectures and orchestration of satellite-terrestrial systems.

A centrepiece of the exhibition highlights Europe’s space ambitions through a mixed-reality model of ESA’s Argonaut lunar lander, designed to deliver cargo to the Moon. Visitors can remotely operate a training rover via a live satellite link, underscoring how Europe’s connectivity infrastructure is intended to support not only terrestrial innovation but also future lunar missions.

Tech

Mobile World Congress Opens in Barcelona With Focus on AI and 5G Concerns

-

Entertainment2 years ago

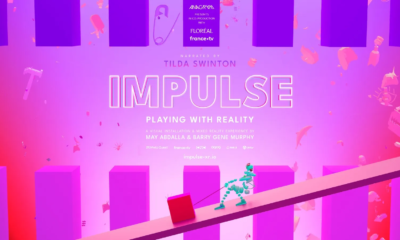

Entertainment2 years agoMeta Acquires Tilda Swinton VR Doc ‘Impulse: Playing With Reality’

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia’s Model for Sustainable Aviation Practices

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoRecent Developments in Small Business Taxes

-

Home Improvement1 year ago

Home Improvement1 year agoEffective Drain Cleaning: A Key to a Healthy Plumbing System

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoWho was Ebrahim Raisi and his status in Iranian Politics?

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoCarrectly: Revolutionizing Car Care in Chicago

-

Sports2 years ago

Sports2 years agoKeely Hodgkinson Wins Britain’s First Athletics Gold at Paris Olympics in 800m

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia: Foreign Direct Investment Rises by 5.6% in Q1