Tech

Militant Groups Adopt AI to Spread Propaganda and Boost Recruitment

Extremist organisations have begun using artificial intelligence (AI) to create realistic images, videos, and audio in efforts to recruit members and amplify their influence, national security experts warn. Since programs such as ChatGPT became widely accessible, militant groups have increasingly experimented with generative AI, despite being unsure how to fully exploit its potential.

Recent reports show that individuals linked to the Islamic State (IS) have encouraged supporters to integrate AI into their operations. One post on a pro-IS forum urged users to make “AI part of their operations,” noting its ease of use and potential to cause concern among intelligence agencies.

IS, which once controlled territory in Iraq and Syria, is now a decentralized network of groups and individuals sharing a violent ideology. The organisation recognized years ago that social media could be a powerful recruitment and propaganda tool, making AI a natural extension of its digital tactics. Even poorly resourced groups or individual actors can now use AI to produce deepfakes and other fabricated content at scale, widening their reach and impact.

“For any adversary, AI really makes it much easier to do things,” said John Laliberte, former NSA vulnerability researcher and CEO of cybersecurity firm ClearVector. “With AI, even a small group that doesn’t have a lot of money is still able to make an impact.”

Militant groups have already used AI-generated content to influence public perception. Two years ago, during the Israel-Hamas conflict, fabricated images showing bloodied children in bombed-out buildings circulated widely online, stirring outrage and polarising audiences. Last year, following an IS-affiliated attack at a Russian concert that killed nearly 140 people, AI-crafted propaganda videos spread rapidly on social media and discussion boards. IS has also produced deepfake audio of leaders reciting scripture and quickly translated messages into multiple languages.

Experts caution that, while extremist groups are still behind nations like China, Russia, or Iran in sophisticated AI applications, their use of the technology is considered “aspirational” but dangerous. Hackers are already using synthetic media for phishing attacks, and AI can also help write malicious code or automate parts of cyberattacks. Homeland security agencies warn that militants could one day use AI to compensate for technical limitations in producing biological or chemical weapons.

Lawmakers are seeking to address the growing threat. Senator Mark Warner of Virginia stressed the need for AI developers to share information on misuse by extremists, hackers, or foreign spies. House legislation now requires homeland security officials to assess the risks AI poses to terrorist groups annually. Representative August Pfluger, who sponsored the bill, said policies must evolve to counter emerging threats.

Marcus Fowler, former CIA agent and CEO of Darktrace Federal, highlighted the urgency: “ISIS got on Twitter early and found ways to use social media to their advantage. They are always looking for the next thing to add to their arsenal.”

As AI becomes increasingly powerful and accessible, security experts warn that militant groups’ ability to manipulate the technology for recruitment, propaganda, and cyber operations is a threat that governments and tech companies cannot ignore.

Tech

ESA and GSMA Launch €100 Million Initiative to Advance Europe’s 6G and AI Ambitions

Europe has stepped up its push to lead in next-generation connectivity with a new partnership between the European Space Agency and the GSMA aimed at strengthening 6G and artificial intelligence capabilities through satellite-based communications.

The two organisations announced at the Mobile World Congress a joint funding programme worth up to €100 million to accelerate the integration of satellite and terrestrial mobile networks, known as non-terrestrial networks (NTN). The initiative marks one of Europe’s most significant public investments to date in hybrid satellite-mobile infrastructure.

Antonio Franchi, head of the 5G/6G NTN Programme Office at ESA, described connectivity as the backbone for unlocking advanced technologies. He said the funding would support the development of networks, services and digital tools that could benefit industries and society at large as digital transformation expands.

The programme is open to companies and organisations based in EU member states, which can apply by submitting formal proposals to ESA. Projects will be selected following an evaluation process.

Funding will focus on four core areas: artificial intelligence-driven management of multi-orbit satellite and ground networks; direct-to-device connectivity for smartphones and Internet of Things devices; collaborative 5G and 6G testing platforms; and early research into edge intelligence and advanced IoT systems.

The types of applications envisioned include telemedicine and telesurgery, autonomous driving systems and precision agriculture, all of which depend on reliable, high-capacity connectivity. By merging satellite coverage with mobile infrastructure, the initiative aims to extend high-speed communication even to remote regions.

Alex Sinclair, chief technology officer at GSMA, said combining the mobile industry’s global reach with ESA’s expertise in space technology would help usher in a new era of connectivity and deliver transformative benefits.

The move comes as global competition intensifies in satellite internet and advanced communications, with US companies currently holding a strong position. European officials say the continent’s strength in high-tech manufacturing and specialised software can offer an independent and competitive alternative.

Several European firms are showcasing their work under the programme at MWC, including Nokia, Filtronic, OQ Technology and MinWave Technologies. Demonstrations include live displays of hybrid network architectures and orchestration of satellite-terrestrial systems.

A centrepiece of the exhibition highlights Europe’s space ambitions through a mixed-reality model of ESA’s Argonaut lunar lander, designed to deliver cargo to the Moon. Visitors can remotely operate a training rover via a live satellite link, underscoring how Europe’s connectivity infrastructure is intended to support not only terrestrial innovation but also future lunar missions.

Tech

Mobile World Congress Opens in Barcelona With Focus on AI and 5G Concerns

Tech

Transatlantic Tensions on Digital Rules Highlight Need for Cooperation

Discussions between Europe and the United States over digital regulation continue to be marked by miscommunication and frustration, even as competitors observe from the sidelines. Europeans and Americans talk past each other while rivals watch. The European Union can set its own standards, but in an interconnected economy, decoupling fantasies and grandstanding won’t help.

The debate often centres on “free speech” concerns voiced by U.S. tech companies and policymakers in response to the EU’s legislative framework for digital platforms. In Europe, such narratives typically prompt defensive reactions. Some Europeans respond with a blunt message: “This is our land, our Union, our laws, follow them, or leave the EU—we’ll find alternative products to use!” Public awareness of American constitutional amendments is low across Europe, just as Americans pay little attention to European digital acts and regulations.

The transatlantic dialogue is further complicated by the global nature of social media platforms. Any EU legislation affecting user experience inevitably influences the functioning of these platforms worldwide, touching on what Americans see as free speech rights. The EU also seeks to extend its influence through the “Brussels effect,” ensuring that European rules shape global standards, while the U.S. maintains a large trade surplus in services and competes technologically with China. This mix of economic, political, and regulatory factors explains why U.S. attention is sharply focused on Europe’s digital policies.

Europeans argue that their 450-million-consumer market has the right to set rules that reflect local principles and values. Attempts to adjust or simplify regulations are difficult, with efforts often met with political resistance and scrutiny. The regulatory ecosystem in Europe supports industries of lawyers, consultants, and experts whose work depends on maintaining complex rules, making reform a sensitive topic.

On the American side, anti-EU rhetoric by public figures has sometimes compounded the problem, drowning out moderates and reinforcing defensive European responses. Analysts note that both regions have seen productive voices sidelined as grandstanding and negative statements dominate public discourse.

Observers argue that long-term thinking is necessary. By evaluating the EU-U.S. tech partnership in the broader context of global alliances, including China and Russia, policymakers can better assess priorities and avoid unnecessary disruption. Blank-slate decoupling between Europe and the United States is unrealistic, and delaying constructive dialogue risks broader economic consequences.

Experts warn that continued transatlantic infighting benefits other global powers and weakens the ability of both regions to set coherent standards in emerging technologies. The message from analysts is clear: cooperation, not confrontation, will determine whether the EU and U.S. can maintain leadership in digital regulation while safeguarding economic and technological interests.

-

Entertainment2 years ago

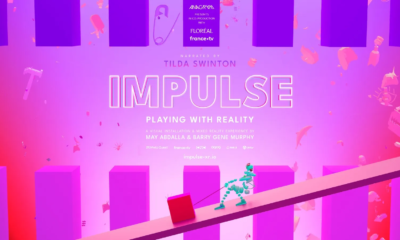

Entertainment2 years agoMeta Acquires Tilda Swinton VR Doc ‘Impulse: Playing With Reality’

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia’s Model for Sustainable Aviation Practices

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoRecent Developments in Small Business Taxes

-

Home Improvement1 year ago

Home Improvement1 year agoEffective Drain Cleaning: A Key to a Healthy Plumbing System

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoWho was Ebrahim Raisi and his status in Iranian Politics?

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoCarrectly: Revolutionizing Car Care in Chicago

-

Sports2 years ago

Sports2 years agoKeely Hodgkinson Wins Britain’s First Athletics Gold at Paris Olympics in 800m

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia: Foreign Direct Investment Rises by 5.6% in Q1