Health

Third Measles Death Reported in Texas Amid Worsening U.S. Outbreak

An unvaccinated 8-year-old child has died from measles complications in Texas, marking the third confirmed measles-related death in the United States this year as the country battles a growing outbreak. The child was from a community experiencing a significant surge in cases and passed away on Thursday, according to a hospital spokesperson.

This latest fatality comes amid a troubling resurgence of the highly contagious disease, which is preventable through vaccination. Health officials say that the outbreak in Texas began in late January and has since escalated, with the state reporting another sharp increase in cases and hospitalizations on Friday. Nationwide, the U.S. has already seen more than twice the number of measles cases reported in all of 2024.

Texas has become the epicenter of the outbreak, though several other states are also seeing active transmission, particularly in communities with low vaccination coverage. The majority of cases have occurred in children, many of whom are unvaccinated.

Measles, a virus that spreads through the air via coughing, sneezing, or even breathing, can be especially dangerous for children. While most recover, complications such as pneumonia, brain inflammation, blindness, and even death can occur. The U.S. had previously reported two measles-related deaths this year: a 6-year-old child in Texas in February and an adult in New Mexico in early March.

Measles was declared eliminated in the United States in 2000, thanks to widespread vaccination efforts. However, recent years have seen vaccination rates decline in some areas, leading to renewed outbreaks. Public health officials stress that at least 95% of a community must be vaccinated to maintain herd immunity and prevent the virus from spreading.

So far in 2025, there have been 607 confirmed cases of measles across 21 states, according to U.S. health data. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warns that if the trend continues, the outbreak could extend into next year.

Global health officials are also expressing concern over rising measles cases worldwide. In 2023, an estimated 10.3 million people were infected, and 107,500 died from the disease. Europe is experiencing its worst measles outbreak in 25 years, with over 120,000 cases reported across the continent and Central Asia last year. Romania currently leads with the highest number of infections. In the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, more than 32,000 cases have been documented from early 2024 to early 2025.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has urged countries to ramp up vaccination efforts, particularly for children, who account for most of the recent cases. In the U.S., health officials are encouraging parents to ensure their children receive the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, which is over 97% effective after two doses.

Health

Europe Faces Growing Challenges in Meeting Medical Care Needs, EU Report Shows

A new report has highlighted stark disparities in healthcare access across Europe, revealing that a growing number of citizens face unmet medical needs due to systemic issues such as high costs and long waiting times.

According to the latest data from Eurostat and the Health at a Glance: Europe 2024 report, 3.8 per cent of EU residents aged 16 and over reported unmet medical needs in the past year. However, the percentage climbs significantly when focusing solely on individuals who actively required healthcare services — with some countries reporting unmet needs among over 20 per cent of this group.

The causes are twofold: healthcare system barriers, including long waiting lists and treatment costs, account for 2.4 per cent of all cases, while 1.4 per cent stem from personal reasons such as fear of doctors, lack of time, or lack of knowledge about available care.

Unmet healthcare needs vary widely across the continent. Estonia tops the list within the EU, with 15.5 per cent of people reporting unmet needs, followed closely by Greece and Albania, each over 13 per cent. Even wealthier Nordic countries show surprising figures — Denmark (12.2 per cent), Finland, and Norway (over 7.5 per cent) — despite high healthcare spending. Conversely, countries such as Germany (0.5 per cent), Austria (1.3 per cent), and the Netherlands (1.4 per cent) report the lowest levels, pointing to more efficient and accessible healthcare systems.

Cost is a dominant barrier in nations like Greece and Albania, where over 9 per cent of citizens cited unaffordable care. In contrast, long waiting times are the primary issue in countries like Estonia (12 per cent) and Finland (7.5 per cent).

Income inequality also plays a major role. On average, 3.8 per cent of low-income individuals across the EU report unmet needs due to healthcare system issues — more than triple the 1.2 per cent reported by higher-income groups. In Greece, that gap is particularly wide, with 23 per cent of low-income respondents affected.

Healthcare experts say these disparities reflect more than just economic factors. Dr. Tit Albreht, President of the European Public Health Association (EUPHA), noted, “Unmet health needs arise from different reasons, including how well healthcare governance integrates services to meet population needs.”

Industry leaders, such as Tina Taube of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA), stressed the importance of timely access to diagnosis and treatment. “Unmet needs are context-specific,” she said. “It’s not just about product availability, but also healthcare system readiness.”

Andy Powrie-Smith of EFPIA added that patients in some European countries wait up to seven times longer than others for the same treatments due to regulatory delays and varying national infrastructures.

The findings underscore the need for a more coordinated, equitable healthcare strategy across the continent, especially as Europe faces the challenges of an ageing population and increasingly complex medical technologies.

Health

Chinese Nationals Charged in U.S. with Smuggling Toxic Fungus Labeled a Potential Agroterrorism Threat

U.S. federal authorities have charged two Chinese nationals in connection with smuggling a dangerous agricultural fungus into the country, a move investigators describe as posing significant national security risks.

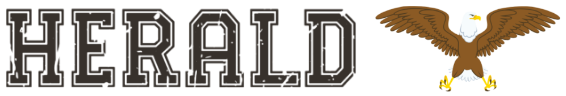

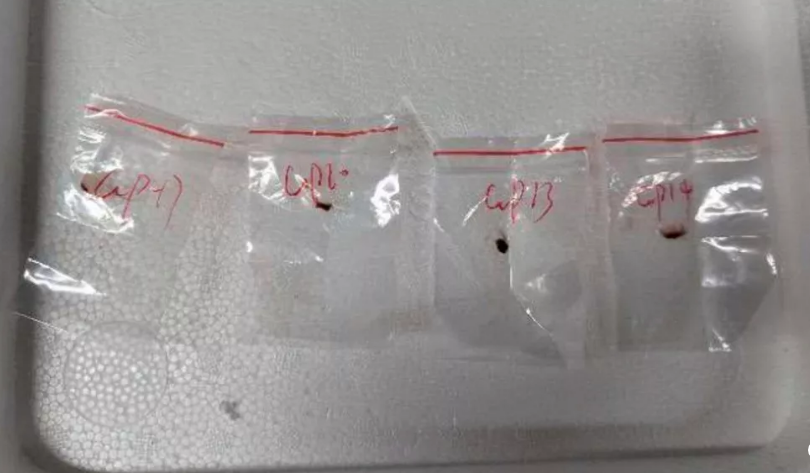

Yunqing Jian, 33, and Zunyong Liu, 34, are accused of conspiracy, smuggling, making false statements, and visa fraud after allegedly attempting to bring Fusarium graminearum — a toxic fungus capable of devastating crops and harming humans and livestock — into the United States. The case was detailed in a court filing by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in Detroit.

The fungus, which targets essential food staples like wheat, maize, barley, and rice, is described in a scientific journal cited by the FBI as a “potential agroterrorism weapon.” Experts warn that its spread could inflict serious damage on global food security and agricultural economies.

U.S. Attorney Jerome Gorgon Jr. emphasized the seriousness of the case, stating: “The alleged actions of these Chinese nationals, including a loyal member of the Chinese Communist Party, are of the gravest national security concerns.”

Jian made her first appearance in a Detroit federal court on Tuesday and remains in custody awaiting a bond hearing scheduled for Thursday. A court-appointed attorney for her initial appearance declined to comment.

According to the FBI’s complaint, the investigation began in July 2024 when Liu was stopped at Detroit Metropolitan Airport. During a routine screening, customs officials discovered suspicious red plant material in his backpack. Liu initially claimed not to know what it was but later admitted he planned to use it for research purposes at the University of Michigan, where Jian is currently employed and where Liu previously worked.

Authorities say Liu’s mobile phone contained an article titled “Plant-Pathogen Warfare under Changing Climate Conditions,” raising further concerns about the intended use of the samples. The FBI believes the two individuals were coordinating to introduce the pathogen into a U.S. research setting without proper clearance or oversight.

Liu was denied entry to the U.S. and deported in July. Charges against both individuals were filed this week, as prosecutors continue to investigate the scope of the alleged conspiracy.

The case underscores growing concerns in the U.S. over biosecurity and potential misuse of scientific research amid rising geopolitical tensions.

Health

US Expands Measles Vaccination Guidance Amid Global Surge in Cases

-

Business1 year ago

Business1 year agoSaudi Arabia’s Model for Sustainable Aviation Practices

-

Business1 year ago

Business1 year agoRecent Developments in Small Business Taxes

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoWho was Ebrahim Raisi and his status in Iranian Politics?

-

Business11 months ago

Business11 months agoCarrectly: Revolutionizing Car Care in Chicago

-

Business11 months ago

Business11 months agoSaudi Arabia: Foreign Direct Investment Rises by 5.6% in Q1

-

Technology1 year ago

Technology1 year agoComparing Apple Vision Pro and Meta Quest 3

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoIndonesia and Malaysia Call for Israel’s Compliance with ICJ Ruling on Gaza Offensive

-

Sports10 months ago

Sports10 months agoKeely Hodgkinson Wins Britain’s First Athletics Gold at Paris Olympics in 800m