Health

Global Obesity Rates Expected to Soar by 2050, Study Warns

A new study published in The Lancet projects that by 2050, nearly 60% of adults and 31% of children and young people worldwide will be overweight or obese, marking a sharp increase from previous decades. The research highlights a growing health crisis, with experts warning of serious consequences for global well-being.

A Worsening Trend

According to the study, 3.8 billion adults and 746 million young people are expected to be overweight or obese by mid-century. This marks a significant rise from 1990 figures when 731 million adults and 198 million young people were classified as overweight or obese. The findings show that each new generation is gaining weight earlier and faster than before.

For example, in high-income countries, 7% of men born in the 1960s were obese by the age of 25, but this percentage increased to 16% for men born in the 1990s and is expected to reach 25% for those born in 2015. This trend is fueling an epidemic linked to type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and certain cancers.

Emmanuela Gakidou, one of the study’s authors, called the obesity crisis a “monumental societal failure.”

Global Hotspots for Obesity

The study identified several countries as obesity hotspots. In 2021, over half of the world’s overweight or obese adults were concentrated in just eight countries:

- China (402 million)

- India (180 million)

- United States (172 million)

- Brazil (88 million)

- Russia (71 million)

- Mexico (58 million)

- Indonesia (52 million)

- Egypt (41 million)

Future growth in obesity rates is expected to be driven by population increases in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Among high-income nations, the United States, Chile, and Argentina are projected to have the highest obesity rates. In Europe, Greece is forecasted to have the highest levels of obesity by 2050, affecting 48% of women and 41% of men.

Impact on Healthcare Systems

As obesity rates climb, so do associated health risks. The study estimates that by 2050, one in four obese adults worldwide will be over 65, adding further strain on global healthcare systems. The effects are already being felt in countries like the U.S., Australia, and parts of Europe, where obesity-related health complications are lowering life expectancy and quality of life.

Despite these alarming trends, research suggests that only 7% of countries worldwide have healthcare systems prepared to tackle the rising obesity-related health burdens. Experts warn that without intervention, obesity will continue to drive millions of premature deaths annually from conditions like diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and stroke.

Rising Obesity Rates Among Young People

The research also paints a troubling picture for younger generations. While most young people in 2050 are expected to be overweight rather than obese, childhood and adolescent obesity rates are set to increase by 121%.

Obesity is expected to rise sharply in North Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and the Caribbean, as well as in large nations such as the U.S. and China. Among high-income nations, Chile is forecasted to have the highest childhood obesity rates, while the U.S. will lead in obesity among young adults (ages 15-24). In Europe, Greece and San Marino will have the highest rates among boys and girls, respectively.

Dr. Jessica Kerr, one of the study’s authors, emphasized that interventions are still possible, saying, “If we act now, we can prevent a complete transition to global obesity for children and adolescents.”

Calls for Policy Changes

Experts argue that addressing the crisis requires more than just medical treatments. The study measured obesity using body mass index (BMI), a widely used metric, but one that some researchers say should be replaced with more precise health indicators.

Meanwhile, new weight-loss drugs, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists, have been hailed as potential game-changers, but experts caution that medications alone cannot stop the obesity epidemic.

Johanna Ralston, CEO of the World Obesity Federation, warned that tackling obesity requires comprehensive policy changes. Strategies such as food labeling, taxation on unhealthy foods, and better urban planning to encourage physical activity are crucial to combating the crisis.

“We can’t just treat our way out of it. We need to change the way we approach food and exercise as a society,” Ralston said.

The findings underscore the urgent need for a global, multi-pronged strategy to address the obesity epidemic before it becomes an even greater public health catastrophe.

Health

FDA Clears AI Tool to Improve Detection of Fetal Abnormalities in Ultrasounds

A new artificial intelligence software designed to enhance prenatal ultrasound screenings has received clearance from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), offering a potential boost to the detection of fetal abnormalities.

Developed by the American start-up BioticsAI, the tool integrates with existing ultrasound machines to analyze images in real time, highlighting potential issues during scans. Prenatal ultrasounds are widely used throughout pregnancy to identify potential problems in a developing fetus, including malformations in organs or limbs. Yet studies suggest that routine scans can miss a significant number of abnormalities.

According to research, a single early scan performed between 11 and 14 weeks of pregnancy detects only about 38 percent of birth defects. A mid-pregnancy scan, typically conducted between 18 and 24 weeks, identifies roughly 51 percent of abnormalities. When both scans are performed, detection rises to 84 percent, leaving a remaining gap in diagnosis.

BioticsAI’s software works by analyzing each fetal image as it is captured. It evaluates image quality, suggesting adjustments to ensure a clear view of the fetus, and checks whether all parts of the baby are visible. Using data patterns drawn from a global database, the system can detect anomalies, including heart or limb defects, and flag them for the doctor during the scan. After the examination, the software generates a report compiling all findings for clinical review.

Developers say the tool can also save healthcare professionals roughly eight minutes per patient in documentation time. The FDA’s clearance confirms that the software meets medical device performance standards and can be safely integrated into current ultrasound systems.

The approval comes amid ongoing challenges in prenatal care. In Europe, major congenital anomalies occur in about 23.9 per 10,000 births. AI-driven tools are emerging as a promising supplement to conventional scans. French companies Diagnoly and Sonio Detect have also received approval for AI-assisted ultrasound solutions, which automatically identify fetal structures and detect potential heart issues.

Experts say integrating AI into prenatal care could improve early detection rates and help doctors provide timely interventions or monitoring. Real-time feedback during scans ensures that images are complete and abnormalities are less likely to be missed.

BioticsAI’s FDA-cleared tool is expected to be rolled out in clinics across the United States, offering clinicians an additional layer of support in detecting congenital abnormalities. As AI technologies continue to expand in healthcare, prenatal care is emerging as a key area where machine learning can complement human expertise, improving outcomes for both mothers and babies.

Health

Early Flu Wave Hits Europe as Experts Offer Tips to Ease Symptoms

Most people catch a cold in winter, battling fatigue, runny noses, sneezes, coughs, and congestion. This season, an unusually early flu wave has affected millions across Europe, prompting health authorities to offer guidance on managing symptoms.

Typically, influenza season runs from mid-November to late May. However, figures from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) indicate that cases in 2025 surged three to four weeks earlier than in the previous two seasons. The agency reports that flu circulation remains high, though it has recently peaked in most regions.

While there are no specific cures for the flu and the common cold, some simple measures can help manage symptoms and improve comfort. Experts recommend a combination of hydration, rest, and symptom relief to support recovery.

Drinking enough fluids is particularly important. Water, broths, and warm beverages with honey, lemon, or ginger can help prevent dehydration, loosen mucus, and soothe irritated airways. Health authorities caution against alcohol, coffee, and other caffeinated drinks, which can act as diuretics and worsen congestion and sore throats.

Gargling with warm salt water is another simple measure to ease throat pain and reduce inflammation. Mixing one teaspoon of salt in a cup of warm water and using it several times a day can provide relief and help clear mucus.

Rest is essential for recovery. Adults are advised to sleep seven to nine hours a night, and to take naps as needed to allow the immune system to combat the virus. Light exercise such as short walks or yoga may be suitable for mild symptoms, but physical activity should be avoided if fever is present or chest symptoms worsen, to prevent complications.

Maintaining moisture in the environment can also alleviate symptoms. Dry air worsens congestion and sore throats, while humidified air hydrates airways and helps clear mucus. Higher humidity can also reduce how long some respiratory viruses survive in the air.

Medicines can relieve symptoms but do not cure viral infections. Decongestants, such as saline sprays or drops, can ease nasal congestion. Painkillers, including ibuprofen, may reduce fever and discomfort in adults. Antibiotics are not effective against colds or flu and should be avoided to prevent antibiotic resistance.

Health authorities emphasize that these measures, combined with good hygiene and vaccination where appropriate, are key to limiting the impact of seasonal viruses. The ECDC notes that most healthy adults recover from flu within about a week, while a common cold may last up to two weeks.

With the early flu wave affecting millions across Europe, simple steps such as staying hydrated, resting, and taking appropriate symptom relief can help patients recover safely and reduce strain on healthcare services.

Health

Climate Change Drives Respiratory Illness, Push for Low-Carbon Inhalers Grows

As climate change worsens respiratory diseases, doctors and drugmakers are exploring earlier diagnosis and low-carbon inhalers to cut emissions from care and protect patients.

For millions of people worldwide, climate change is already affecting breathing. Rising air pollution, longer pollen seasons, and smoke from wildfires are contributing to asthma attacks, lung damage, and other chronic respiratory illnesses. At the same time, the health systems treating these conditions are themselves contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

Experts note that over 90 percent of the global population breathe air with particulate levels above World Health Organization recommendations. Climate extremes and poor air quality are increasing the frequency and severity of respiratory diseases, from exacerbations to disease onset. Therese Laperre, head of the respiratory department at University Hospital Antwerp, said changes in particulate matter can trigger emergency visits for asthma and chronic pulmonary diseases days later. A European Environment Agency study estimated that more than a third of chronic respiratory disease deaths in Europe are linked to environmental factors such as pollution, extreme temperatures, wildfire smoke, and allergenic pollen.

Worldwide, an estimated 400 to 500 million adults live with COPD, and over 250 million have asthma. Health care responses come with their own climate cost. Health Care Without Harm estimates global health services generate about five percent of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, which could rise to six gigatons annually by 2050 if unchecked, equivalent to more than a billion cars on the road. Hospitals, particularly intensive care units, are among the most carbon-intensive, due to high energy use, equipment, and single-use materials.

Respiratory specialists emphasize that early disease control benefits both patients and the environment. Philippe Tieghem from the French respiratory association Sante Respiratoire said early diagnosis allows for better patient care while reducing emissions.

Inhalers, commonly used to treat asthma and COPD, illustrate the challenge. Traditional pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) use hydrofluorocarbon propellants, which contribute 16–17 million tonnes of CO₂-equivalent emissions globally each year. The UK’s National Health Service estimates these inhalers account for around three percent of its carbon footprint.

Pharmaceutical companies are developing greener alternatives. AstraZeneca’s reformulated COPD inhaler uses a new propellant, HFO‑1234ze(E), cutting its global warming potential by roughly 99.9 percent compared with older devices. The company has pledged to reduce its emissions by 98 percent by 2026, starting with inhalers. Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson have committed to net-zero targets by 2040 and 2045, respectively.

Pablo Panella, senior vice-president for respiratory diseases at AstraZeneca, told Euronews Health that early detection, diagnosis, and treatment keep patients controlled in the community, reducing hospital admissions and the high-carbon interventions that come with them. Panella also stressed the importance of regulation that supports innovation, allowing low-carbon technologies to reach patients more quickly.

Better disease control, combined with environmentally conscious products, is creating the concept of the “green patient”: someone whose chronic condition is managed well enough to avoid repeated flare-ups, hospital stays, and carbon-intensive treatments.

-

Entertainment1 year ago

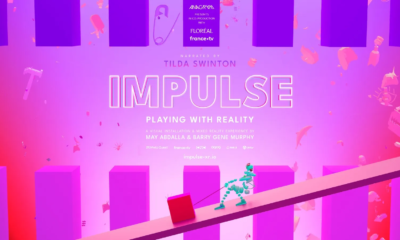

Entertainment1 year agoMeta Acquires Tilda Swinton VR Doc ‘Impulse: Playing With Reality’

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia’s Model for Sustainable Aviation Practices

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoRecent Developments in Small Business Taxes

-

Home Improvement1 year ago

Home Improvement1 year agoEffective Drain Cleaning: A Key to a Healthy Plumbing System

-

Politics2 years ago

Politics2 years agoWho was Ebrahim Raisi and his status in Iranian Politics?

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoCarrectly: Revolutionizing Car Care in Chicago

-

Sports1 year ago

Sports1 year agoKeely Hodgkinson Wins Britain’s First Athletics Gold at Paris Olympics in 800m

-

Business2 years ago

Business2 years agoSaudi Arabia: Foreign Direct Investment Rises by 5.6% in Q1